“This American carnage stops right here and stops right now.”

–From Donald Trump’s Jan. 20, 2017, inaugural address

That is the first of what turned out to be thousands of lies from Trump during his term as U.S. president. Spoken only minutes after he assumed the powers of the office, it was in fact the start of his American carnage. That includes his incompetent handling of the COVID-19 pandemic, now with more than 350,000 U.S. deaths.

I’ve reached out for reactions to the Trump-stoked anarchy in Washington, D.C., including historical parallels and contemporary Irish media views,. which begin below the photo, newest at the top. I will update this post over several days. MH

Jan. 8 updates:

CNN’s Donie O’Sullivan, native of Cahersiveen, County Kerry, became a social media sensation for the way he held his nerve and gave clear and concise updates amidst the Trump mob on Capitol Hill.

While the eyes of the world watched mayhem unfold in Washington last night, Kerryman @donie became a social media sensation in Ireland as he reported live from the scene for CNN | https://t.co/goIQuPz2zg pic.twitter.com/VOqa88B0Gq

— RTÉ News (@rtenews) January 7, 2021

***

This was a manifestation of weakness and eclipse, though Trump should not expect to escape legal consequences for inciting an attack on democracy, the shock troops involved praised by him as “patriots”. Impeachment? Probably impossible in the 12 days he has left in office. But prosecutors need to look at possible charges.

—Editorial in The Irish Times

Jan. 7 updates:

Mick Mulvaney, Trump’s former acting chief of staff turned special envoy to Northern Ireland, resigned from the post in the wake of the “international travesty” that took place at the Capitol. “I can’t do it. I can’t stay,” he said.

***

“This was not a moment of madness. It was a show for which Trump had been running trailers for at least a year. This was never a dark conspiracy. It was an undisguised insurrection. Trump’s one great virtue is his openness.”

—Finton O’Toole in The Irish Times

***

Former Miss Universe Ireland Fionnghuala O’Reilly was followed and harassed by a Trump supporter as riots unfolded in Capitol Hill, the Irish Independent reported. She said that the man followed and yelled at her for wearing a mask while out for a run.

***

“The Irish people have a deep connection with the United States of America, built up over many generations. I know that many, like me, will be watching the scenes unfolding in Washington DC with great concern and dismay.”

–Tweet from Irish Taoiseach Micheál Martin

***

The Irish Post and other media report that Trump could be headed to his golf resort in Doonbeg, County Clare, a day before Joe Biden’s Jan. 20 inaugural. Scottish First Minister Nicola Sturgeon has said Trump is not allowed to visit his course in that country.

Original Jan. 6 post:

Police in the US Capitol Jan. 6 responded with drawn guns and teargas as hundreds of protesters stormed the building and sought to force Congress to undo President Donald Trump’s election loss shortly after some of Trump’s fellow Republicans launched a last-ditch effort to throw out the results.

–Early report in the Irish Independent

***

“Shocking & deeply sad scenes in Washington DC – we must call this out for what it is: a deliberate assault on Democracy by a sitting President & his supporters, attempting to overturn a free & fair election! The world is watching! We hope for restoration of calm.”

–Tweet by Irish Minister for Foreign Affairs Simon Coveney

***

“Trump’s conduct reminds me of Ian Paisley in the old days in Northern Ireland. Whip up followers to violence, then wash hands and walk away when violence breaks out.”

— John Dorney, editor of the The Irish Story

***

“The closing chapter of Donald Trump’s presidency was never going to conclude quietly. After four tumultuous years in the White House, the outgoing president is continuing his attack on the norms of American democracy right up to the end.”

—Irish Times Washington correspondent Suzanne Lynch in Jan. 5 column, before the unrest at the U.S. Capitol.

***

“I never thought I would see such scenes in America.”

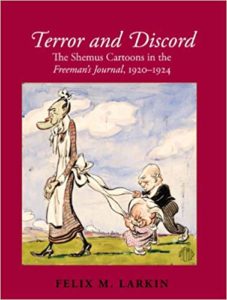

–Dublin historian Felix Larkin.

He passed along a 2014 BBC story about the “Burning of Washington” by British Army Maj. Gen. Robert Ross, from Rostrevor, of County Down. It was the only time that a foreign power captured and occupied Washington. This time it was domestic.