Fifty years ago this month the American book publisher Doubleday released Ireland: A Terrible Beauty, by Jill and Leon Uris. The couple had traveled on both sides of the partitioned island from May 1972 (four months after Bloody Sunday) to January 1973.

Leon, an established author, conducted research for a new novel, Trinity, which became a best seller when it was released in 1976. Jill, his third wife, 23 years younger, photographed nearly 400 images of thatched cottages, mist-shrouded countryside, and gritty scenes of urban violence; in color, and in black and white.

Their Preface says:

“We were lured there by an intriguing people, their sometimes magnificent, sometimes harsh land, and, mostly, their poignant history. Our aim was to find the keys to that story which would clarify so much of the mystery and puzzlement of recent events and simultaneously photograph everyone and everything wherever the search took us. …

“Ireland is too vast and complex in its story for two people to cover it comprehensively in less than a decade. We made no pretense at attempting to.

“What we do have here is a social, historical, and political commentary on what we consider to be the guts of the matter of a unique people and their lovely but sorrowed island. This is our point of view on the “troubles” that have plagued Ireland for the fatter part of a millennium.”[1]Leon Uris and Jill Uris, Ireland: A Terrible Beauty. The Story of Ireland Today (With 388 Photographs, Including 108 in Full Color). [Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1975]. … Continue reading

The couple covered 10,000 miles, mostly by auto, “on some decent and some indecent roads.” Their journey and their book recalled American photographer and antiquarian Wallace Nutting, who estimated he and his wife covered 700 miles in all 32 counties 50 years earlier, during the summer of 1925. Nutting’s book, Ireland Beautiful, was published in time for that year’s Christmas gift-giving. It featured 304 half-tone engravings of Irish landscapes—only six images show people—and his text in support of the title.

From his studio near Boston, Nutting wrote:

“This volume pretends to no place as a guide book, nor is its text intended to cover with precision or fullness any part of Ireland. It is merely a record of impression of beauty or quaintness, observed in a land which for romance and pathos, strange history and legend, for witching grace and mystery, is probably unsurpassed.”[2]Wallace Nutting, Ireland Beautiful. [Norwood, Mass.: The Plimpton Press, 1925]. 302 pp. Quoted from Foreword.

Though he began his career as a Congregationalist minister, Nutting insisted his book had “nothing whatever to do with political and religious matters.” He noted the work of the Boundary Commission, which later in 1925 fixed the partition line in place, and made sweeping, uncontroversial generalizations: “The people of Ulster were as insistent on remaining in the empire as South Ireland was on withdrawing from the empire.”[3]Ibid., 286.

For more on Nutting, see my August 2025 piece for History Ireland, “Ireland Beautiful–How A 1925 American Photobook Boosted Irish Tourism.”

More opinionated

Leon Uris was more opinionated in his analysis of an Ireland then descending deeper into sectarian strife, rather rather the island emerging from a war of independence and civil war at Nutting’s visit. During the Uris’s nine-month stay, more than 400 people were killed and thousands of others were injured in shootings and bombings. More than 500 people were charged with terrorist offences. “Their visit coincided with one of the most violent years of the Troubles,” wrote biographer Ira B. Nadel.[4]Ira B. Nadel, Leon Uris: Life of a Best Seller. [Austin: University of Texas Press, 2010], See Chapter 9, “Ireland,” 209-232.

Uris leveraged his identity as an American Jew, not an Irish-American of Catholic or Protestant faith, as well as his status as a celebrity author. He took particular aim at “the most diabolic by-product of three hundred and fifty years of the plantation of Ulster, a cancerous growth known as Paisleyism.” Grimly, he concluded: “The nightmare of Ulster has come about with Christian fighting Christian in one of the most advanced of Western societies. Continuation of this travesty with God can lead to the eclipse of civilization in that part of the world.”[5]Uris, Terrible Beauty, 128, 195.

The Troubles got much worse, of course, but not quite that bad.

By coincidence, Terrible Beauty’s November 1975 release was three months after the death of Éamon de Valera, the most consequential leader of twentieth century Ireland. The book says he “had the full measure of that detached, ruthless arrogance, political guile, persuasiveness, and total self-assurance that stamp greatness on a national leader. He was the rarest breed, the head of a small country that has achieved stature among the political giants of this century.”[6]Ibid., 162.

Photographing Ireland

Dev’s death ends the book’s 8-page chronology, which begins in 10,000 BC when the island emerged from the receding Ice Age. Naturally, the book included a map and, like the island itself, was divided into two sections: The Republic and Ulster.

“Photographing in the Republic was almost always a joy. Ulster was another story,” Jill Uris wrote. She described the difficulties of working in the sectarian maelstrom of the North as a woman and an outsider. Her “Photographing Ireland” in the Appendix also contains notes about the pre-digital camera equipment she used during the assignment.[7]Ibid., 209-212

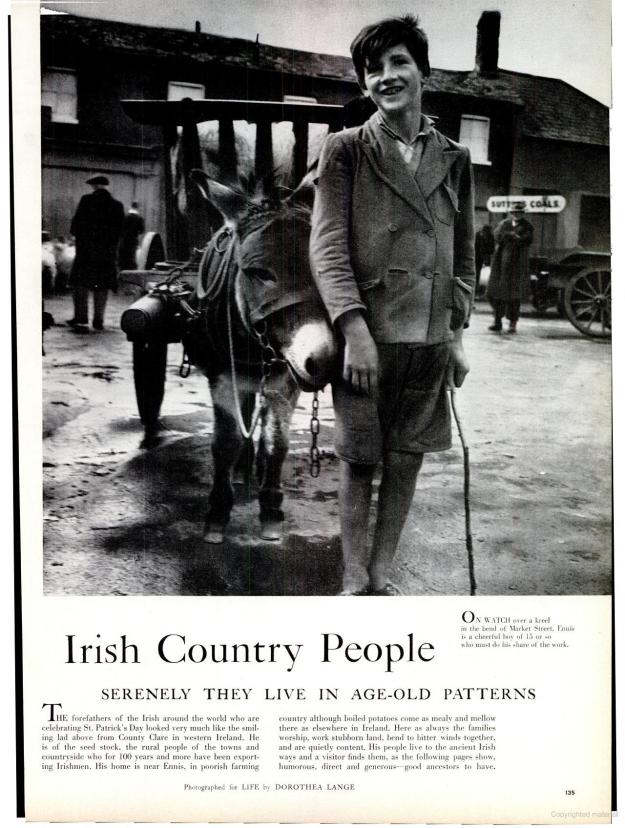

Aside from the images of sectarian violence in the North, most of Jill’s photographs show a mid-twentieth century Ireland without much hint of the rapid modernization that would arrive in the coming decades, and certainly since 2000. In this regard her images of the country are similar to those of American photographer Dorothea Lange, who arrived in County Clare in September 1954 on an assignment for Life magazine. See my September 2024 post, “Remembering Dorothea Lange’s ‘Irish Country People’“.

I’ll return to my exploration of the Uris’s visit and their work in future posts.

References

| ↑1 | Leon Uris and Jill Uris, Ireland: A Terrible Beauty. The Story of Ireland Today (With 388 Photographs, Including 108 in Full Color). [Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1975]. 288 pp. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Wallace Nutting, Ireland Beautiful. [Norwood, Mass.: The Plimpton Press, 1925]. 302 pp. Quoted from Foreword. |

| ↑3 | Ibid., 286. |

| ↑4 | Ira B. Nadel, Leon Uris: Life of a Best Seller. [Austin: University of Texas Press, 2010], See Chapter 9, “Ireland,” 209-232. |

| ↑5 | Uris, Terrible Beauty, 128, 195. |

| ↑6 | Ibid., 162. |

| ↑7 | Ibid., 209-212 |